Laci Mosier is a poet and fiction writer living in Brooklyn, NY. Her text art has appeared in Hobart, The American Journal of Poetry, Tupelo Quarterly, and others. Her work has been nominated for Best Small Fictions and named a finalist for the Tobias Wolff Award for Fiction. She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Jocelyn Winn: What draws you to the poetics of erasure, given your foundations as a fiction writer?

Laci Mosier: I work a lot in very short stories, and so I find a natural parallel between the process of making erasure poems and flash fiction. They both require you to peel back as much as possible and see what’s left. Everything not on the page is as important as what is. I feel like that’s true of many of our most important conversations, too. There’s a lot of life left in the gaps.

Of course, with erasures, you’re constrained to working with just the words in front of you, even the order of them is already decided for you. I love the challenge of filtering through the text to find little leaps, connections, and surprises. The possibilities feel endless, and yet there are finite words to work with. Sometimes, the right ones snap into place immediately; sometimes, it takes weeks or months. The erasure process is quite physical: You’re circling, erasing, and clearing debris. And there’s the permanence of it as well—once you bring out the Sharpie or the Wite-Out, there’s no going back. Sometimes, you wipe out a word you didn’t intend, which can be devastating. But sometimes, it is delightful when a new meaning you never planned for takes shape. It’s messy, and you just have to work with that. There’s not a backspace. And in a strange way that’s freeing.

JW: There’s a big push nowadays to do away with genre boundaries and having to name categories. Is this true for the field of literary artwork as well?

LM: Definitely, I think the lines between text art, erasures, collages, graphic novels, and comics are always sort of blurry. In my experience, writers working in these mediums are always figuring out where and how they fit. Sometimes the distinctions are pretty rigid for what journals want to publish. Sometimes they’re more fluid. I like that there’s overall a growing interest in blending different genres, and I think anything combining text and art is already bending the rules of literature in its own way.

JW: You know I am absolutely fascinated by your process of assemblage—I liken it to a temporary art installation. Once it is dismantled, it exists only as it was documented by photo or description. Can you explain your process and what inspired it?

That’s such a beautiful way to describe them—temporary art installations. I discovered and fell in love with this medium and process during a residency in New Mexico. I was staying on a remote farm in San Cristobal in a cabin that D.H. Lawrence used to write in. I had very limited Wi-Fi or cell reception and a pile of vintage magazines. I found myself staying up until 1 a.m. every night feverishly slicing up pages, configuring layouts, and gluing pieces down and I loved that process—it’s very demanding and dynamic. It’s always thrilling when you find yourself so absorbed in anything that you lose all sense of time.

By the end of that residency, I was making pieces so quickly that I began to just layer them with plans to glue later. And that’s when I started to notice the way the pieces sort of had a floating quality, the edges of the paper curling in some spots, natural bends in spots were lifting visual elements off the page. The pieces started to have a delicate, living quality when they weren’t glued down, but rather just layered. From there, I began to work pretty exclusively in this ephemeral way. I, of course, meticulously store all the elements of each piece so the originals can be re-created in a more permanent way when needed.

JW: I see similarities in your flash fiction and erasures in an exquisite minimalism whose meaning is anything but stark. A pool noodle, a T-shirt, a Band-Aid can each take on epic proportions. Can you speak to using found objects both in your prose and poems?

LM: Oh yes, I’ve never thought about how the found objects that appear in much of my fiction relate to the found text I use in my poems, but that’s a cool observation. I think I enjoy the hunt of a good find. I grew up going to garage sales and still have an affinity for them. Rummaging through people’s things—through their lives—feels so personal, like pressing your cheek against a stranger. The privateness of such objects makes them especially fascinating to me. Each little object, whether kept or tossed, can tell a whole wide story. I like to think about what those stories and the motivations behind them may be.

JW: Short-form writing especially demands we pour over words and choose mightily and carefully. How do you practice restraint in omitting text to create blank space, and how do the visual pieces fill in those blanks?

LM: The cutting and erasing is merciless when working in the short form. To me, that’s the burden and also the beauty. It’s actually quite freeing to see how many words can get sliced off a piece and for it to still have a beating heart. In text art, this is also about balancing the visuals with the negative space.

Deciding what gets to stay and what gets to go can feel like a puzzle. I like to start by yanking out big paragraphs or scenes and setting them in a blank Word doc. At first, the cutting can feel like you’ve taken off a big toe or a whole limb, but often I find the piece still stands, maybe even a little stronger, after you’ve pared it back. Once I believe a piece is ready, I push myself to cut an additional 10–20%. The prose usually rises to the occasion, with each word working even harder than before.

For erasures, the visuals get to do a lot of heavy lifting, allowing you to get away with a leaner poem. Sometimes their role is overt, other times it leaves just a hint of subtext. That’s a cool tool that you don’t have access to in traditional literature.

JW: You enact several motifs and patterns in your erasure series, namely birds, for instance, or subverting outdated advertising images. Do you know the themes or social messages beforehand or do they emerge as you create, much like characters eventually take on a life of their own?

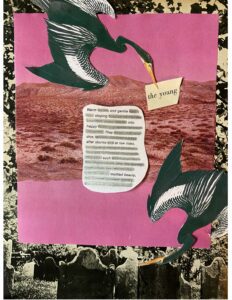

The Young, 8″ x 11″, 2021

LM: When I start a series, I’m always intrigued by the images and motifs that draw me in. I definitely get hyper-fixated on certain subjects and go at them full tilt. The themes and social messages aren’t planned though, at least not at a conscious level. They usually emerge slowly after I’ve already made a handful of pieces; I start to notice the reverberation between them later. Sometimes the themes arrive first as text, other times they are in the visuals first. I do think that’s where the subconscious starts to roll up its sleeves and stitch the pieces together.

Each series definitely takes on a life of its own. And sort of like writing characters for fiction, I have to be mindful to try and not force them to be what I want, because it will always feel off. For example, in my Learning to Fly series, I initially envisioned the birds as representations of women, but in the end they seemed to demand to represent the patriarchy instead. I stopped resisting and allowed that narrative to unfold and the pieces became more subversive and surprising. At times, I feel as though the elements and my impulses are teaching me about myself, uncovering the heavy parts of my heart. Right now, I’m fixated on ears, noses and feet. The body.

JW: How much does place or landscape play in your work? You’re firmly rooted in Texas but have lived in Brooklyn for some time now. And you’re an avid traveler. All those observations must inform your aesthetic.

LM: Oh definitely. All my life, place has affected me so deeply. Not just landscapes, but smells, sounds, vibrancy, tastes, pace, plants, the times of sunrise and sunset—all of it sort of tugs at different strings of the psyche.

Living in Brooklyn can feel like sensory overload just getting a cup of coffee. You can step on a dead rat and be moved to tears by a busker singing all within five minutes. Yet amid the chaos, there’s also a rhythm. Some days, it’s like living in a jazz riff; others are a sad trombone. It’s fast and wild and exciting and hard and that tension of loveliness and horridness definitely comes through in my work.

Life in Texas, on the other hand, is quieter, more expansive. Literal tumbleweeds roll across the highways where I grew up and the sunsets and the stars stretch as far as the eye can see. There’s a raw, rugged beauty and a connection to nature that soothes a deep part of my soul. Stepping onto the grass in my parents’ front yard, I feel a stillness that anchors me in the most special way.

I carry all of these worlds in my heart when I come to the page. A lot of my work explores a clash of chaos and calm. Delicate and disgusting.

JW: Any advice for emerging writers and artists on how to cultivate an erasure practice or perhaps where to look for publishing or gallery representation?

LM: Start small with low stakes. Rummage through Free Little Library stands or old books that aren’t precious to you, pick a page at random, and see which words rise off the page for you. Don’t read the page first; keep the process more stream of conscious versus analytical. I find that if you’re too familiar with the existing material, it will bog you down. Just skim and start circling words with a pencil and see what happens. Like any writing form, leave room for surprise and don’t be afraid for it to suck.

Most of all, enjoy the process. I find that working with my hands versus typing on a keyboard offers a sort of magic. I think it’s satisfying and cathartic and innately playful. In that way, I think it can be a beautiful way to stay in conversation with your soul and see what words and themes tug at you. See what your subconscious mind wants to tell you. Mary Ruefle said that for her, the right words levitate off the page, hovering a couple of inches. But maybe it’s just some words you like, and maybe those words together offer something special.

Thank you Laci!!!!

Find Laci Here:

- @lacibeeeee